He was born into an old bell-making family in Jelšava and learned the trade in his father's workshop at the end of a period when bell production in this town was one of the most significant economic sectors. Jelšava benefited in those times from the proximity of ironworks in the northern, mountainous areas, from where sheets of iron were imported...

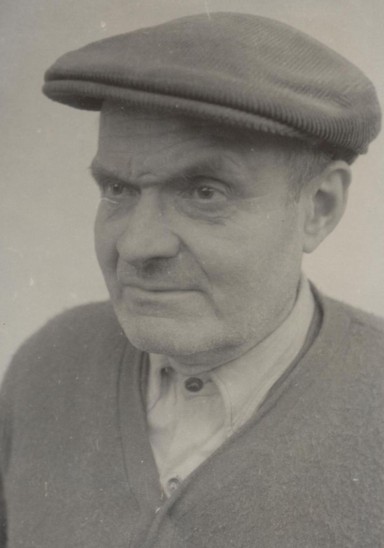

He was born into an old bell-making family in Jelšava and learned the trade in his father’s workshop at the end of a period when bell production in this town was one of the most significant economic sectors. Jelšava benefited in those times from the proximity of ironworks in the northern, mountainous areas, from where sheets of iron were imported to the town. The bells made from them were distributed throughout the former Kingdom of Hungary, as well as to the Balkans, Asia, the Middle East, and Egypt. This state of affairs was disrupted by the First World War and the reorganization of political relations afterwards, resulting in the slow decline of bell craftsmanship in Jelšava, eventually leaving its sole representative – though all the more famous – Ľudovít Kenyeres.

He definitively decided on bell-making at the age of fifteen, choosing it over further schooling. He began actively producing bells in 1914. Over more than half a century of his active craft life, he made tens of thousands of bells. Among shepherds and collectors across Slovakia and abroad, who simply called him the Jelšava bell-maker, their wide range of different types and shapes, but above all, the quality of their sound, made him famous.

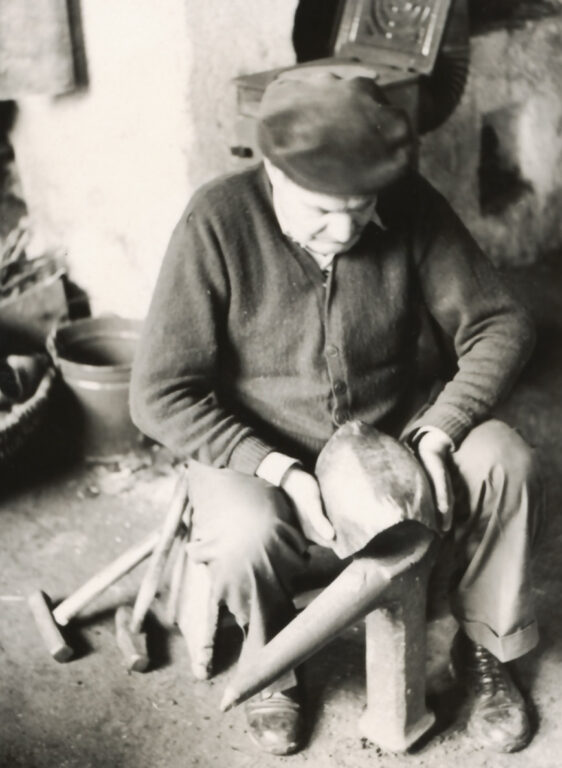

In production, he used an ancient technological process. First, he measured the sheet according to the desired bell size and determined the central point, which in the next step formed the so-called bell horn. This was followed by bending and shaping the sheet, known as “puklovanie,” then removing irregularities, smoothing the sheet, bending it, and punching holes for riveting. Kenyeres performed this stage cyclically, and when he had enough bells shaped, he proceeded to rivet them. After attaching the ear and heart of the bell, he coated them with clay mixed with brass, ensuring a good connection of the sheets during subsequent riveting in the fire. Once dried, he placed them in groups of 10-15 into a furnace, reaching the high temperature needed to melt the brass using charcoal and a bellows. After 15-20 minutes, he removed the bells from the furnace and rolled them on the ground to evenly spread the melted brass over the entire surface. An advantage of the Jelšava bell-makers was that the local clay contained magnesite and could withstand high firing temperatures. The only caution needed was to ensure that the furnace temperature was not too high and did not overheat the iron sheet. The fired bells were then cooled with a stream of water, followed by removing the clay shell and cleaning the bells. The pinnacle of the production process, considered the greatest mastery of bell-making, was tuning the bells by tapping the sheet on a curved anvil, a technique closely guarded by each manufacturer.

In 1960, Ľudovít Kenyeres was awarded a qualification as a master of folk art production in the metal industry for his craftsmanship, making him one of the first to receive such recognition.