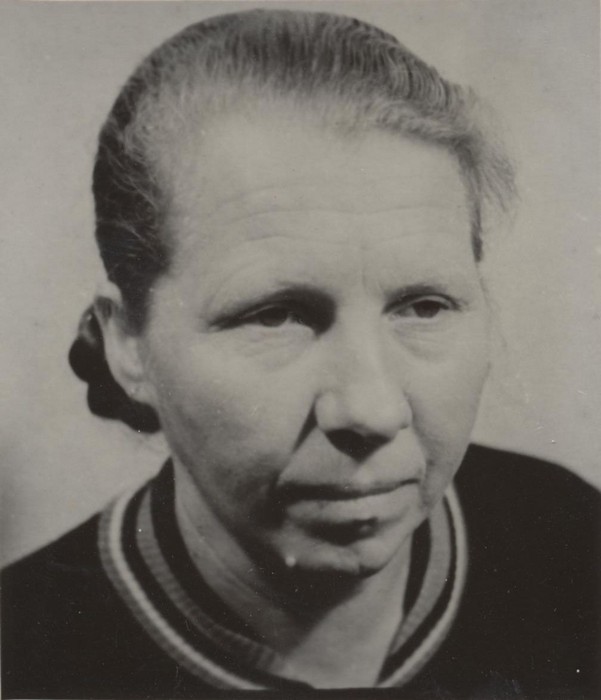

Stefánia Dudáková, born in Domaniža in 1912, found success with her multicolored batik Easter eggs already as a young girl. Girls and women sought her out during the Easter period to have their eggs decorated, and in her determination to satisfy everyone, she worked tirelessly day and night. The ornamental decoration of Easter eggs during her youth was less rich...

Stefánia Dudáková, born in Domaniža in 1912, found success with her multicolored batik Easter eggs already as a young girl. Girls and women sought her out during the Easter period to have their eggs decorated, and in her determination to satisfy everyone, she worked tirelessly day and night. The ornamental decoration of Easter eggs during her youth was less rich and complex, with patterns primarily serving as playful inscriptions and wishes for young girls and boys. These inscriptions were mainly painted on the middle circumferential bands with the most even flat surface.

This passion continued into her adulthood, and her husband assisted her in preparing colors and making various tools, while her growing daughters eventually joined in the painting process, later becoming excellent painters of Easter eggs themselves. Her work gained intensity and quality after she began collaborating with the ÚĽUV, who honored her as one of the first masters of folk art in 1962. In the 1950s, she produced 1,400 eggs per year, increasing to 2,400 in the 1970s.

In decorating Easter eggs with the batik technique, she drew upon the rich ornamental tradition of her region and organically developed it, transitioning to more colorful expressions. The ornaments and color compositions aligned with tradition but also reflected the personal touch of the artist, giving the eggs both customary and artistic dimensions.

In Domaniža, batik Easter eggs made with a mixture of paraffin and beeswax in equal proportions (1:1) are known as “inscribed kražlice.” The mixture is applied to the egg’s surface with a tool called a “pisarka,” a simple implement similar to a funnel. Stefánia Dudáková’s eggs stood out for their precise and clean ornament, motifs, and compositions. They ranged from one to five colors, depending on the negative or positive batik method used. In the negative method (multicolored), the egg was dipped into increasingly saturated colors, while the positive method (two-colored) involved applying wax to a dark-colored egg, followed by color removal with vinegar. Dudáková derived colors from plants and inorganic materials (iron shavings, paper scraps, crepe paper), later incorporating aniline dyes from the 1970s.

She creatively developed basic motifs in her ornamentation, ensuring they retained their unique character and emphasizing distinctive details. The line dominated the composition of her eggs, dictating their shape and rhythm. The egg’s surface was symmetrically divided into ornamental bands horizontally or vertically. The central part of the pattern in multicolored eggs was typically the lightest color.

The ornamental elements, motifs, and compositions she used could be categorized as geometric (dots, lines, triangles, squares, rhombuses, strips, semicircles, spirals, coils, etc.), transitioning into motifs inspired by agricultural tools (pitchforks, rakes) or cosmogonic symbols (sun, stars), botanical motifs (scales, shoots, leaves, flowers, etc.) integrated into patterns such as lilies, leaves, thistles, bird heads, or cuckoo flowers, as well as animal motifs featuring hearts, butterflies, spiders, and other designs. Each pattern had a specific name, which was passed down to her successors.

Her selfless dedication to sharing her art is another characteristic that defines this master. Besides her two daughters and children from schools who she dedicated her time to for many years as part of extracurricular artistic activities, she also taught the technique of inscribed kražlice to individuals such as Soňa Belokostolská from Považská Bystrica, who now follows in her footsteps as a master of folk art.

Source: Prandová, E.: Batik Easter eggs of Štefánia Dudáková. In: Národopisné aktuality 3/1988