The manufacturer grew up in a working-class family in Pstruša in Vígľaš. His father was trained as a wheelwright and carpenter, so he had contact with wood from an early age. He also loved folk music and songs – when they were played on the radio, he would dance to them with a valaška in the yard. In the folk...

The manufacturer grew up in a working-class family in Pstruša in Vígľaš. His father was trained as a wheelwright and carpenter, so he had contact with wood from an early age. He also loved folk music and songs – when they were played on the radio, he would dance to them with a valaška in the yard. In the folk art school, he played guitar and keyboards, also performed in the school band, later had no problem with the clarinet or saxophone, and then, as he started making fujaras and flutes, he mastered them too. He got into their production in 1984 through his mom’s brother, Master Peter Paciga, who was looking for his successor. Although he had a son, he was more interested in engines, so he approached his nephews to see if they would be willing to learn. Jozef Svoreň, as a trained welder, spent his entire productive life working at the Podpolianske machines in Detva and had experience with occasional production of carved sticks, valaškas, or belts. His connection to traditional art was strong, so he agreed – and since then, the production of musical instruments never left him.

When he first came to Paciga’s workshop, he was just making a whistle, and he was immediately given wood to try making it. Later, as he got better at making whistles, he also started making his first fujara this way. He still has it stored away and it plays beautifully. However, his uncle scolded him for the way he drew the ornament on it, as they were all the same. He emphasized that ornamentation should never be copied. According to him, you should draw with a free hand, not play with stencils. Today, Ján Svoreň has patterns with Paciga’s designs and his own, but after all these years, he knows them by heart. He only looks for inspiration when he feels that a certain pattern has been repeated for too long. He initially did well. When he had problems, he sought advice from his uncle. This is where his production basics were formed. However, when Peter Paciga passed away in 1985, he had to figure out some nuances on his own. Or through discussions with other manufacturers he knew through Peter Paciga.

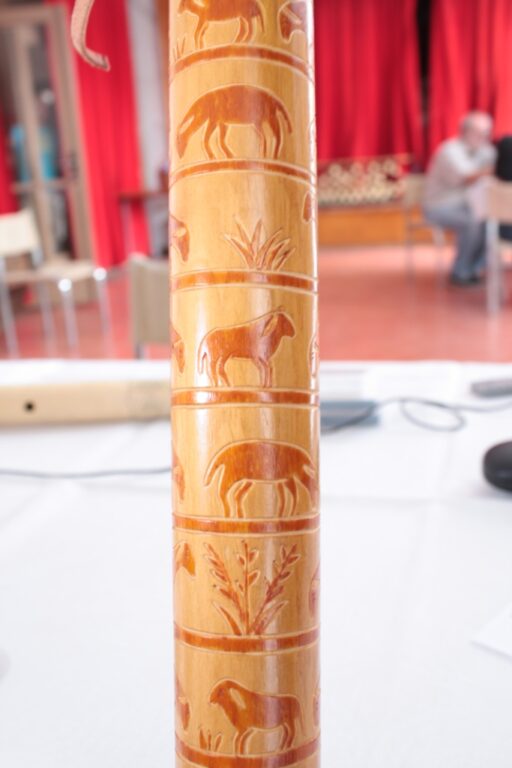

After decades of practice, sound is the top priority for Ján Svoreň. As he says, when you take wood from the mountain for a musical instrument, you are obliged to return its soul through beautiful sound, so that the tree can come back to life. However, this doesn’t mean he has given up on decorating the instruments. On the contrary, he preserves the traditional Podpolianske decoration with carved ornaments, subsequently burnt with nitric acid, also known in the region as “šalvajster.” Bamboo has proven to be the most effective for him when applying it to wood, and he uses a V-profile rubber gouge for carving grooves. Lately, he has also been experimenting with decorating by stamping wood with metal punches. His main range includes fujaras and six-hole flutes, but if there is demand, he will also make endpieces (which were not traditionally made in Podpoľanie), twin flutes, or a stick that has three uses (as a stick, a flute, and after covering the holes, as an endpiece). Well-prepared production tools are the basis for quality work for him. He made most of them himself – marking tools made from metal pipes, knives, and gouges, only bought drills. He sharpens the tools himself with fine sandpaper and brass polish. Sharpness is crucial for him – as he says, you need to cut once and precisely.

He is happy to share the secrets of production with people who show interest.

Crafting musical instruments is not a means of getting rich for him, rather a passion – and moreover, he did not have to pay to gain knowledge, so why keep it to himself? Currently, he has two apprentices from the garages in the Detva housing estate, neighboring his workshop, and his nephew, Peter Paciga’s son, also comes to learn from him. If he perseveres, Jozef Svoreň would be pleased – the knowledge would stay with the Pacigas, and he could hang up the production with a clear conscience, knowing he has a successor