The manufacturer grew up in Jahodníky near Martin and from an early childhood, he was close to the sound of the fujara and shepherds' whistle. Later, it was the sound of bagpipes, instrument ends, or whipper snippers that were close to him, and he was also close to the production of ladles, rakes, belts, shepherd caps, embroidered fur coats, chains...

The manufacturer grew up in Jahodníky near Martin and from an early childhood, he was close to the sound of the fujara and shepherds’ whistle. Later, it was the sound of bagpipes, instrument ends, or whipper snippers that were close to him, and he was also close to the production of ladles, rakes, belts, shepherd caps, embroidered fur coats, chains for Detva hats, and for sewing cloaks. Alongside his practice, he systematically expanded his knowledge through studying available literature and frequent visits to the museum in Martin, where he had the opportunity to see this beauty and richness firsthand.

At thirteen, he began making a large Detva fujara. Although it did not play like the modern ones, it played, and that was a signal for him to continue, enriching his portfolio with other folk musical instruments. His production and musical models were masters from the Turiec, Orava, Liptov, and Detva regions. In 1978, he participated for the first time in the fujara makers’ competition “Instrumentum excellens”. His instruments appealed to the professional jury, and at his debut at this prestigious event, he immediately won the “Ladislav Leng Prize”. He was awarded this prize many more times in the following years for other musical instruments.

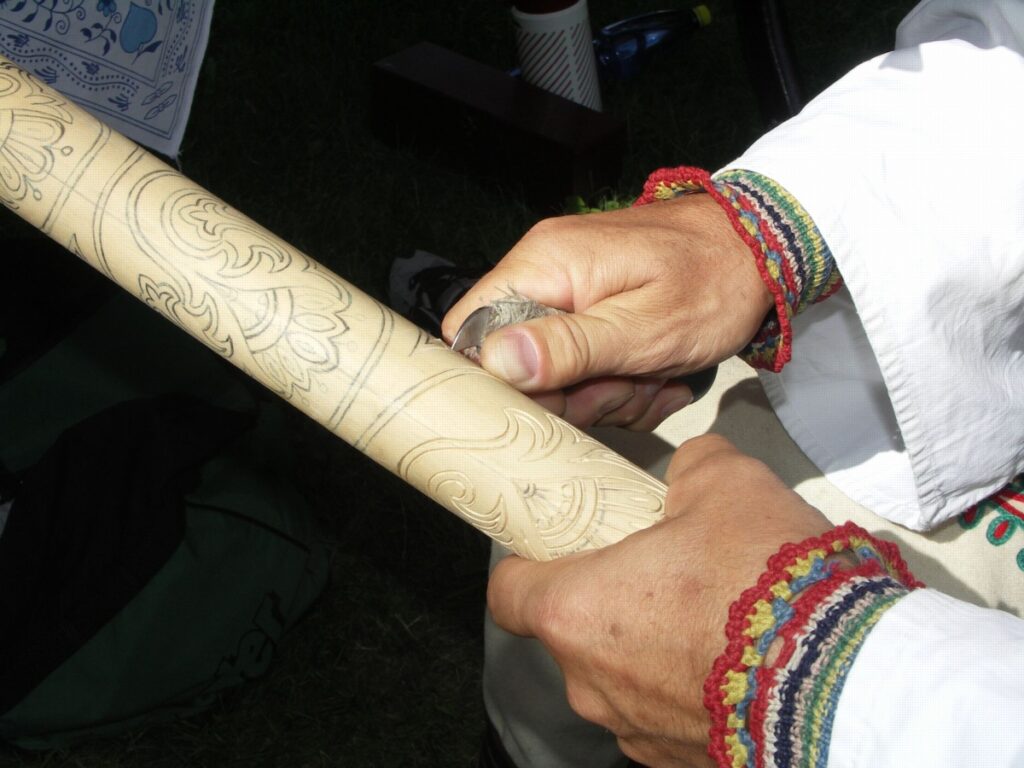

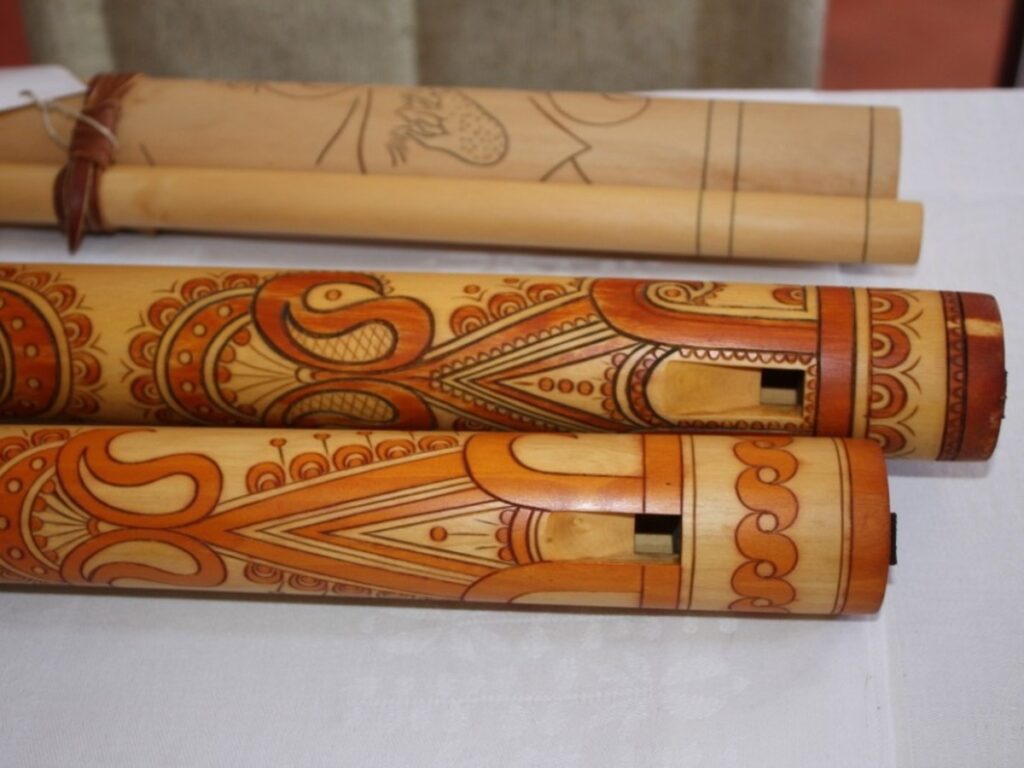

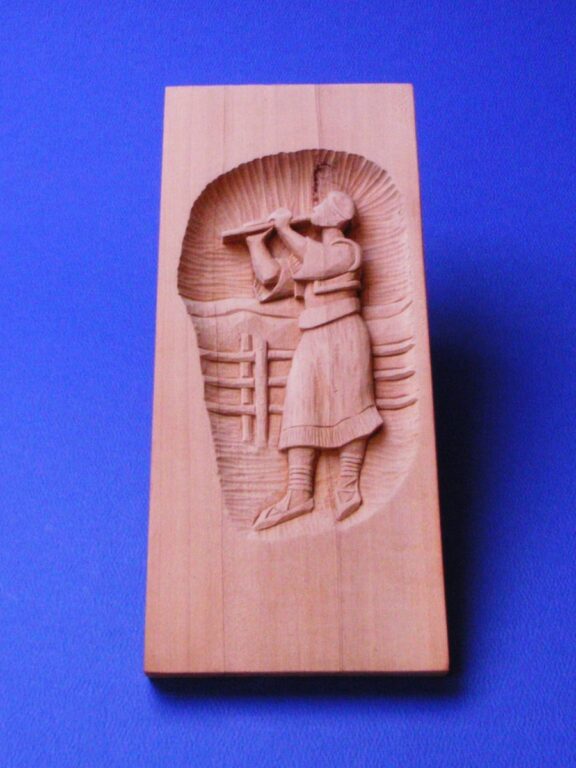

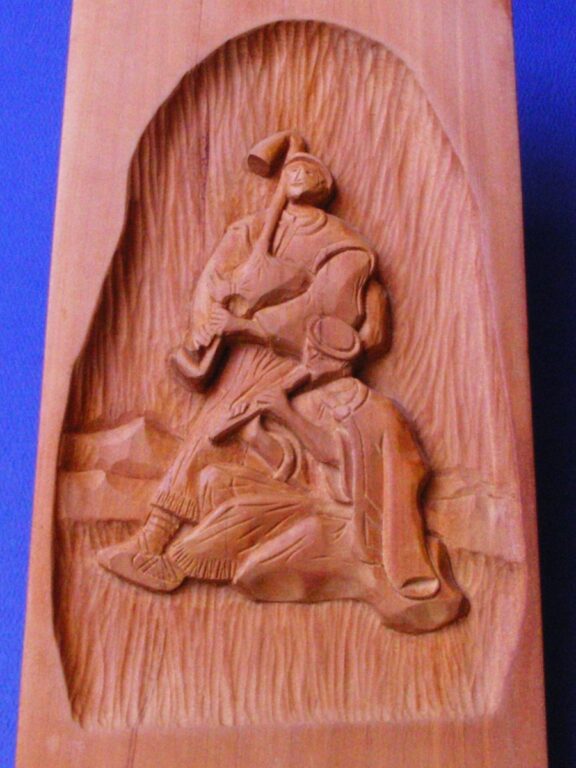

From the beginning of his work, he has remained faithful to traditional manufacturing technologies, always basing his work on honest preparation and understanding of the issues, whether in production or in the case of musical instruments, also in interpretation. His goal is to achieve the highest degree of authenticity, so that the result is not only utilitarian but above all valuable. This is his conscious contribution to preserving the treasures of our traditional visual culture in today’s accelerated era, in which some manufacturers reach for artificial materials to simplify their work, for example, using goretex for bagpipe bags. A fine example of Ľubomír Párička’s work approach is his search for the soft, velvety, or muffled voice of the fujara. Based on reflections and experiments, he concluded that the original environment of this instrument is a shepherd’s hut. The smoke from the fireplace colors the fujara or whistle, and the greasy vapors from the boiled sheep cheese are absorbed into the wood of the instruments, preserving them. He always uses base wood for fujaras and whistles, shinbone for whipper snippers, and goat cheek hair for bagpipes. He decorates fujaras and whistles by burning them with nitric acid, applying traditional Podpolian ornamentation. He saturates the surfaces of fujaras and whistles with oil, then rubs them with lard skin, and finally polishes them with a piece of leather. His folk musical instruments have a captivating charm. With their sound and artistry, they appeal to people and contain a piece of human qualities that remind us of the world of our ancestors. Immersed in the immediate contact with the village and nature since childhood, Ľubomír Párička absorbed this unique dimension of life. Thus, in the intimacy of solitude, his instruments whisper a genuine ballad about the Valachian region into the inner turmoil of man, which, although lost from reality, continues to live among us through musical instruments and the master’s craftsmanship.

Ľubomír Párička performed as a musician on folk instruments in folklore ensembles such as Turiec, Stavbár, Partizán, and collaborated with groups such as SĽUK, Lúčnica, the State Chamber Orchestra of Žilina, and the folk orchestra of Ján Berky Mrenica Jr. His long-standing collaboration with composer Svetozár Stračina or with soloist Jozef Peško of the Orchestra of Folk Musical Instruments was precious, as well as with many other artists. And what advice does this still-active master have for potential successors? Listen to the opinions of the old masters and take the best from them for yourself.

In 2012, for preserving and developing the original creation of folk musical instruments, he was awarded the title of master of folk artistic production.

Source: Mikolaj, Tomáš: Masters of the New Millennium [online]. Bratislava: Centre for Folk Art Production, 2020 [cit. 2024-05-29]. Available at: https://uluv.sk/kniznica/digitalna-kniznica/

You can find more about the manufacturer in the article “Ľubomír Párička and his connection to folk tradition” (RUD 1/2013).