A native of Mníchová Lehoty near Trenčín had a close connection to music from a young age. After passing entrance exams to the Academy of Performing Arts, he landed a job as a puppeteer at a theater in Košice in 1980, where he was captivated by the craft of puppet-making. He then spent fourteen years in the vocal group of...

A native of Mníchová Lehoty near Trenčín had a close connection to music from a young age. After passing entrance exams to the Academy of Performing Arts, he landed a job as a puppeteer at a theater in Košice in 1980, where he was captivated by the craft of puppet-making. He then spent fourteen years in the vocal group of the Slovak Folk Art Ensemble (SĽUK), where he also discovered the fujara, which became a vibrant instrument within the ensemble.

He got involved in making fujaras through playing them and, paradoxically, also through crafting bagpipes, which are among the most challenging traditional musical instruments. He had the opportunity to try making fujaras upon returning from military service under the guidance of Prof. Anton Vranka. Although he never made bagpipes afterwards, his desire for creating more musical instruments persisted.

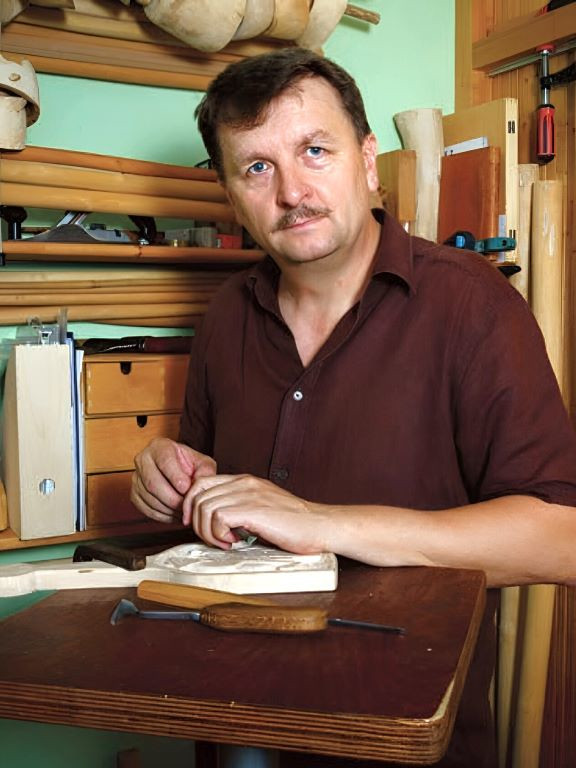

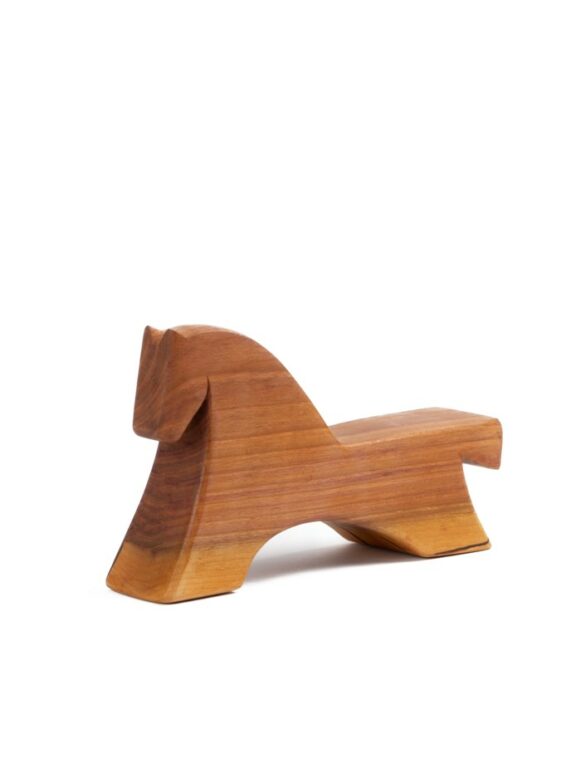

Together with his colleagues from SĽUK – Štefan Kliment, Ján Palovič, and Róbert Kováč – he worked on wooden instruments in a workshop located in a panelák in Petržalka. Starting with whistles, he gradually advanced to fujaras and later to the shepherd’s instruments. Today, his portfolio includes sculptures depicting ordinary rural people from the past, as well as stylized clown figures, toys, and puppets. The essence of his sculptures lies primarily in the facial expressions, influenced by his puppetry experience.

“His musical instruments are characterized by high sound quality. As he says, tuning and sound color are daily aspects of his work – currently, he serves as the second tenor in the Slovak National Theater choir, making sound quality a top priority. However, he quickly adds that when the wood does not want to play, it simply won’t.”

“The fujara belongs to Podpoľanie, so there is no room for artistic speculation. Anything can be carved on it, but personally, I prefer to preserve traditional patterns and ornaments, creating in their spirit. If the wood possesses beautiful natural patterns, I do not embellish it, only polish and burnish it to bring out its structure,” says Ľuboš Straka about the equally important artistic aspect of instrument-making. “However, I am increasingly moving away from traditional acid etching. Decorating one fujara takes me twelve hours, and when I inhale the fumes and have to sing at work later, I feel like my voice is muffled, which lasts for three to four days.”

He gradually developed his own unique technique of decorating instruments with spirit stains and subsequent burning. The classic double cut, used to create pattern lines, is emphasized with darker stains and filled with lighter colors. Although spirit stains do not have the color stability of acid, their nuances emerge over time with continued use. For surface finishing, he applies a base of beeswax oil, followed by a shellac coating to enhance the gloss.

For Ľuboš Straka, working with shepherd’s instruments is an adventure in sourcing the materials and crafting them. As he enjoys woodcarving as a hobby, he only uses hand tools, reflecting the challenging nature of working with such an unyielding material like shepherd’s bowls.

He enjoys adapting to each material with every product he creates, looking forward to the work. Each piece of wood has its own soul. Unveiling and transforming it into something new motivates him to continue creating.

Source: Mikolaj, Tomáš: Masters of the New Millennium [online]. Bratislava: Centre of Folk Art Production, 2020 [accessed May 29, 2024]. Available at: https://uluv.sk/kniznica/digitalna-kniznica/

In 2014, he was awarded the title of Master of Folk Art Production in the field of musical instrument production.